On the occasion of Bookmobile’s thirty-third birthday, our social media maven Nicole Baxter asked me to write up our Origin Story. As I am saving extensive fact checking, memory checking, and actual research for the multi-volume hardcover edition, I guarantee errors. If I have omitted you, I apologize: you deserve to be included and will be in the print version.

Paleotypography

Bookmobile evolved in the Paleocomputer era, before the ascendance of the personal computer, and long before the iPhone was a gleam in Steve Jobs’s eye. (Well, maybe not the latter, as he was born in ’55.) The machine used for creating book pages was the phototypesetter, which created rows of letters on a roll of photographic paper by flashing light through a spinning film negative that had all the letters of the alphabet in one font, one weight, and one size. The timing of the flash was controlled by a computer of the sort that one nowadays might find providing intelligence to a disposable toy. After the roll of photographic paper was exposed in this way, it was run through baths of reeking darkroom chemicals in a machine and hung up to dry. The pages were then scissored apart.

A Compugraphic 7500 phototypesetting machine at the Museum Industriële Archeologie & Textiel, in Ghent, Belgium. Photo was not credited but may be by Laurens Leurs.

In the early ’80s I had a brand new BA in English literature and couldn’t quite figure out what I was going to do next. Needing employment I fell back on skills I had learned in the printing trade in San Francisco in the ’70s, working for graphic services companies south of Market. Pitching my services to the Twin Cities Reader back in Minneapolis I found that the Reader’s production manager, David Tripp, was an acquaintance I had met the year previous at a New Year’s Eve party on Goldmine Hill in San Francisco. Looking for an exit from his Reader job, he quickly arranged for me to replace him. We became fast friends. Both of us were actually much more interested in books than in newspapers.

As it happened my sister Nancy was in the book business, working at the University of Minnesota Press. She composed scholarly monographs on a typesetting machine of a lineage that was about to go extinct: the IBM ESC Composer. Basically this was a Selectric typewriter with proportional letterspacing. When you wanted to switch from roman to italic or back, or any other font change, you stopped typing and replaced the font ball—a metal golfball-sized sphere with raised letters instead of dimples—with one of the needed font. IBM ceased making parts for this gadget, so Bev Kaemmer, the Press’s production manager and my sister’s boss, was looking for phototypesetting vendors. Consequently, in 1982 Nancy and I joined forces to start a company called Alphabet Express, providing book design and typesetting services. Bev was our first great customer: one who insisted that vendors have a keen eye for quality—as well as wield a sharp pencil. Nancy and I knew what quality was, and knew what a book ought to look like, having grown up in a peripatetic household whose moves always included dozens of boxes of my Idaho grandfather’s substantial leatherbound library, plus the books our parents had accumulated. We learned how to sharpen our pencils.

I lined up investors: mainly David Tripp and his wife Ruth, who generously and very optimistically provided seed money in the early days, and for all the years since, moral support. David went with me to the Secretary of State’s office in Saint Paul to register the new corporation. Forgetting the significance of the date, March 17th, we decided to have lunch at O’Connell’s on Grand Avenue. In those days, Saint Paulites took the business of Saint Patrick’s Day very seriously. We had lunch in a booth, and sat there, with suitable number of excursions given the amount of Harp consumed, for the next ten or more hours. By the end of a very long evening, the booth—which could comfortably seat four—had some number of inhabitants north of six, including me and David. The the entire place was literally wall-to-wall with revellers at midnight.

The next day was a day of rest.

The right hand door is 542 Selby Avenue, Saint Paul, where Bookmobile started making books in 1982.

Startup: Book Compositors

Nancy and I found an office in a storefront at 542 Selby Avenue in Saint Paul which, besides being close to home, had an added advantage in the form of the entertainment provided by the occasional drug bust across the street. We added more customers, mostly by word of mouth, because I could not bear to make a cold call. Al Ominsky at the Minnesota Historical Society Press took a chance on us, and we typeset many books for that press. Bob Dubois, then proprietor of Voyageur Press, had us put together books for him. Professor Odd Lovoll came to us for help producing the publications of the Norwegian American Historical Association, a venerable scholarly organization founded in the ’20s by Ole Rolvaag, author of the great book on the settling of the prairies, Giants in the Earth. We owe a great thanks to all of them.

Osborne 1: the first portable computer, weighing in at 23.5 pounds. We used them to prepare book manuscripts for page composition.

Our real opportunity, as it turned out, was in the nascent business of turning author’s word processing files into typeset book pages. Most typesetters didn’t want to screw around with files from Wordstar or any of the other rudimentary software editors that authors were beginning to use. We made a specialty of scraping book content from oddball disk formats and programs. There were lots of them: some 50-odd disk formats and a dozen word processing programs (this was before Microsoft secured its monopoly and winnowed everything down to Windows and Microsoft Word). My first wife Judy Ogren and her sister Denise Schoster helped prepare dozens of raw manuscripts for transformation into typeset book pages, using the 23-lb. portable computer of the day, the Osborne 1.

Our first hire was an expert typesetter, Mary Ellen Buscher, who had been my boss at the Minnesota Daily student newspaper. My sister Nancy moved on because we had become more of a typesetting service than a book design studio, which was her main interest. The business grew, despite my aversion to phone calls, and in 1983 we moved near the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis to a tiny office in a nice building owned by Frank Harris, whose brother John and John’s wife Molly became clients with their imprint Pogo Press. Soon we had six or eight employees stepping all over each other in our tiny office, and so we moved down the hall to a slightly bigger space. Reflecting the fact that we were providing print buying services in addition to typesetting, we changed the name of the company to Stanton Publication Services, Stanton being my middle name.

Ultimately we outgrew that office, and moved in 1988 to another one up the road next to the giant grain elevators in southeast Minneapolis. We hired Wendy Holdman, who had once been my boss at City Pages, and Sarah Purdy, who had also worked there. Wendy later became our production manager, and Sarah is currently our color department manager. I reached the pinnacle of my incompetence with our accounting, and we hired Connie Klotz, who later moved on to the great Saint Paul indy bookstore Hungry Mind and was replaced by her neighbor Mary Oakley.

Culpepper Press

In the late ’80s, David Tripp and I started a book publishing company of our own. We called it Culpepper Press. (David’s middle name is Culpepper. Hmm, seems to be a pattern here.) Culpepper Press was a separate venture from Stanton, but used its services for print production. We found a publicity expert, Ellen Watters, to join Culpepper Press as a partner. We heard through the bookstore grapevine—David was now working at Hungry Mind—that a guy named Stu Abraham, having just sold his book sales commission group to his former partner, was thinking of getting into publishing. Stu joined Culpepper. We published twenty or so books and were distributed by Publishers Group West. We invested a lot of borrowed money in books that didn’t sell and discovered ourselves inadvertently the publishers of a line of coloring books that did sell. Our borrowed capital finally ran out and we ceased publishing new titles, but kept some of our titles in print for another year or so.

In 1991, we leased new space back across the Saint Paul line in the Chittenden-Eastman Building, a seven-story nineteenth-century warehouse built of brick and massive pine timbers. Other tenants included a multitude of artists with tiny studios, assorted eccentric pickers and dealers in ephemera, Graywolf Press—of renown even then—newly moved from their tiny digs on Selby in Saint Paul, and Bookslinger, the small press wholesaler that ultimately gave birth to Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, still the premier indy distributor for avant imprints, despite being swallowed up by Perseus.

By this time we had two semi trailers full of phototypesetting equipment, files, light tables, and furniture. It began to snow as the movers loaded up in Minneapolis, and the snowfall intensified as they arrived at the medieval loading dock of the Chittenden-Eastman Building. The forecast was 22 inches. There was some urgency on the part of the movers to get unloaded and get on the road. We were to pay for overtime. The freight elevator to the seventh floor broke down. (Broken elevators were to be a theme of our years in the CE Building.) It took hours for the elevator to be repaired, while snow accumulated faster and faster. The movers finished at dark, their rigs leaving deep ruts in the new snow as they left the parking lot. The Stanton crew went home.

The next day, the cities of Saint Paul and Minneapolis stood stock still. Over 28 inches of snow had fallen, and more was on the way. I skied to work that Friday from Saint Anthony Park, a mile and a half away, to set up the phototypesetting machines so we could get back to work making books on Monday.

While we were in the CE Building, a guy named Will Powers called one day to take me out to lunch. Will, a typographer, was working for Campbell Mithun Esty, one of the big ad agencies in town. He wanted to come work for Stanton to make books. Understanding the large pay discrepancy between the ad business and the book business, I was skeptical, but we eventually worked something out. Will was a typographer who had started in a letterpress shop in New Hampshire. He had an expert eye, vast knowledge, and was incredibly productive. An artist and a book person through and through, he brought a new dimension to the company. He later moved on to the Minnesota Historical Society Press and became a leading light at the Association of American University Presses before his early death in 2009 at a family cabin in Ontario.

Enter the Macintosh

We were now entering the era of the Macintosh, and Pagemaker. Pagemaker was of no use to us, given the strict typographic requirements of our clientele and Pagemaker’s primitive controls. However, it started to make phototypesetters (the machines) obsolete and devalued the hard-won skills of typesetters (the people), because designers would lay out ads themselves rather than marking up typewritten copy for skilled typesetters to set. Because of this, we acquired a raft of top-notch typesetting gear from the advertising department of Dayton’s department store (the parent of Target and B. Dalton Books, later acquired by Barnes & Noble.) Two of Will’s fellow type-people from Campbell Mithun Esty, Nancy Hokkanen and Kim Doughty, found themselves looking for new positions and joined us. Ann Sudmeier and Kyle Hunter joined the typographic staff a couple of years later.

This was a strategically instructive period. The personal computer had allowed authors to type and edit their manuscripts and pretty much demand that publishers deal with whatever bizarre floppy disk they handed over. The Macintosh and Pagemaker, and later Quark Xpress, destroyed the old business of the trade typographer, by allowing designers to directly compose type the way they wanted it. Frankly, it was all very messy. In general, designers’ and authors’ priorities are not aligned in terms of orthography and consistency with those of publishers and, ultimately, readers. Much of the work that we did was clean up: cleaning up author’s fake italics, funky fonts, and misplaced hard returns, as well as mapping the quirky character sets of some fly-by-night software company to those of a sophisticated typesetting machine.

The strategic lesson was: digital technology will eat everything in its path. Anyone with an investment in analog technologies—a lifetime’s worth of litho stripping skills, for example, or ownership of a phototypesetter which, while digitally driven, owed its existence to an analog workflow—needed to get out of the way. So we knew what we needed to do when Quark Xpress began to be seen as the standard for book typesetting. We had the expensive phototypesetting gear hauled away as junk, and we all learned Quark Xpress—which, by the way, ultimately became a great program, compared to the tag-based paleocomputer programs of the phototypesetter manufacturers. (It’s ironic that HTML , a tag-based markup language that strongly resembled the codes used by obsolete phototypesetters, would come to prominence a few years later as the foundation of the Web.). As book compositors, we were insulated compared to the typographers that served the ad agencies: most designers neither had the skills nor the interest in converting messy author files into pristine five hundred page scholarly monographs chock full of footnotes, foreign diacriticals, tables, extract and formulae with 99.999% accuracy for seven dollars a page.

Book Production Management Services

Though our publishing venture Culpepper Press petered out, it had expanded our contacts in the book business. Stu Abraham introduced me to Tom Kelleher, the Massachusetts-based publisher of Faber and Faber U.S., the sister company of the famed Faber and Faber in the U.K. Their production manager was moving on, he said, and would we take over production of all their new titles and reprints? We did. The long distance relationship was perfect: I liked Tom a lot, but he was prone to dramatic gestures like taking me for a spin in his Acura NSX at ninety miles an hour along the quaint colonial byways of Winchester, Mass. Faber & Faber U.S. was ultimately sold to Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

The Faber relationship enabled us to figure out how to efficiently act as the production department for publishers, and that became our new growth area in the late ’80s and early ’90s. We added Milkweed Editions, another one of the great Minnesota literary presses, as a client, and others followed. Another plus of the Faber relationship was the people we worked with: among them, Betsy Uhrig, now an editor at Little Brown; Fiona McCrae, who later took over Graywolf Press and has brought it to stellar heights; and Jane Brown, now a VP at DAP.

Our relationships with publishers brought us more than just business: a number of our long-time staff started their careers in the great internship programs at Graywolf Press, Milkweed Editions, or Coffee House Press.

Digital Book Printing

In 1994, I read an op-ed in the Saint Paul Pioneer Press by David Morris about on-demand manufacturing, in which he proposed that ultimately books would be printed on demand in bookstores. Having a deep familiarity with book printing after ten years of buying printing on behalf of publishers, I thought this was nonsense. But, with the hard-won lessons about the disruptive power of digital technology in mind, I became intrigued. I roughed out the economics of the POD-in-bookstore model utilizing the Xerox Docutech high-speed printer, and incorporating what I knew about the book publishing industry from the Culpepper Press experience. I wrote a white paper that I circulated among a few friends in the book business to get their reactions. The conclusion of the paper was that POD was a poor fit for the existing model of book distribution, but that it had big potential should the model of distribution change.

Around the same time, I entered a master’s program in the geography department at the University of Minnesota. Geography is a rather undisciplined discipline, covering everything from pedology (soil science) to sociological theories of urban development. It fit my undisciplined interests all too well. While working in the computer lab on cartography projects, I stumbled upon a piece of software called Mosaic, which interacted with this thing called the internet to display multimedia pages from remote servers. Also, an undergrad I worked with on a project met this guy from Germany through email and moved to Germany to marry him. This suggested to me that once again, digitally-induced changes were afoot—changes far bigger than how book pages were made.

In September 1996 the Culpepper Press partners—David Tripp, Ellen Watters, Stu Abraham and myself—had dinner at the Dakota restaurant in Saint Paul to celebrate paying off the last of the bank debt from our publishing venture. Stu Abraham asked what was happening with my Print-on-Demand ideas. I said something along the lines of, “Well, if you could sell books on the internet, the economics of POD start to fall into place.”

Stu replied, “Have you heard of this startup called Amazon?”

We immediately began planning to enter the digital printing business. By the end of 1996, with the key assistance of Judy Ogren’s father Bob, a retired letterpress printer, we had put together our digital book printing facility in a back room of the Chittenden-Eastman Building and produced our first job: a bound galley run.

In 1996, digital printing equipment was too primitive to produce a high-quality book, so we focused initially on printing bound galleys, aka “ARCs” or “Cape Cods.” These are promotional copies of books printed and distributed to reviewers and wholesale buyers in advance of the publication of a book in order to drive publicity and advance orders. At that time, these were typically produced on a low-end offset duplicator or copy machine, so while our digitally printed galleys couldn’t match offset-printed books in terms of quality, they were better quality than traditionally-produced bound galleys.

Row of cluster printers in our first printshop in Saint Paul, 1997. We used these to print bound galley pages.

The black-and-white print room at Bookmobile, 2014. Our four offset-quality Océ 6320s are in the middle of the picture.

In the beginning, the print shop consisted of me prepping print files at night and Judy printing and binding during the day, with her father Bob helping out in the bindery. The digital printers we initially used were basically office printers networked together in a cluster, which printed extremely slowly and jammed constantly. As the business grew, we bought improved printers and binding machines, and added staff. Nicole Baxter—now our sales and marketing manager—joined us early on from Hungry Mind Press, an imprint of the bookstore. Xong Lor, a nineteen-year-old from Saint Paul, became our go-to production guy. Tony Houle, now bindery supervisor, followed, along with others. We had growing pains, hitting a wall where we just could not seem to produce more books per month no matter how many people were working. We hired Dieter Slezak, an experienced print production guy, as production manager. Dieter, now our overall operations manager, quickly got production on track.

Right from the beginning, our aim was to print books, not just bound galleys, so we continually upgraded equipment and procedures, hoping ultimately to produce books indistinguishable from those printed on offset presses. This took three or four years. (Now in 2015, with the parallel evolution of digital presses, binding equipment, and our own processes, we certainly match offset, and in some cases—the printing gamut of our digital color presses, for example—can surpass it in quality.) Norton Stillman—owner with Ned Waldman of the regional wholesaler The Bookmen, as well as publisher of Nodin Press—helpfully suggested that we needed a name for this service distinct from Stanton Publication Services, and we came up with Bookmobile. The digital printing operation—Bookmobile—became the largest part of Stanton, and we eventually renamed the whole company Bookmobile to reflect that predominance.

Technically, we do not actually do Print-on-Demand—which involves printing books only in response to an order from an end-user—but short-run digital printing (SRDP), which involves printing quantities from 50-2,000 for storing in a warehouse and replenishing frequently as demand requires. SRDP addresses the long-standing problem in the book business of overprinting, which left publishers in aggregate stuck every year with millions of unsold books. Now publishers have a choice of printing technologies depending on the volume and velocity of sales on each title: true POD, SRDP, and offset.

eBooks

While the onrush of digital technology clearly had implications for the distribution and printing of books, it also promised to change publishing and reading at a more fundamental level. If the internet could be used to sell printed books, why not skip the paper embodiment of the text altogether and sell eBooks, which could be downloaded instantly? Publishing and reading on-screen had been born with Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of the World Wide Web: the eBook was only a logical extrapolation of the concept. In the late 1990s, the first efforts at producing and distributing eBooks sprouted. Every reading device launched in the period stored and displayed pages in a proprietary format. This presented a quandary for book publishers: how were they going to efficiently produce high-quality pages both for print and for who knows how many future eBook formats? To solve this problem, we started a new company called Pagewing, whose purpose was to build a web-based system where publishers could create books as master XML files, and automatically generate high-quality typographic pages for printing, as well as any type of eBook format that might evolve. We raised a lot of money from a venture capital group, Quatris Fund, and built version one of the Pagewing system. We signed great early adopter publishers, including current clients as well as bigger publishers like Houghton Mifflin and Farrar, Straus and Giroux. But Pagewing as launched had severe usability issues; we needed more investment to develop it further. Our venture funders, reasonably enough, said we need to have more publishers sign up before they could justify further investment. Publishers, on the other hand, couldn’t really commit more titles to the system until its feature set was rounded out and it worked better. Classic chicken-or-egg problem. It didn’t help that consumers in droves were resisting purchasing eBooks. Then the dot-com bubble popped, and Pagewing was done, after several years of work and a lot of money invested, both by Quatris Fund and by Bookmobile. Yet another learning experience.

Book Distribution

Ultimately, the fate of digital book printing was tied into book distribution. By the end of the ’90s, the largest POD printer by far was Ingram Lightning Source, which the big book wholesaler Ingram started the year after Bookmobile’s digital print service with help from IBM’s Boulder, Colorado high-volume digital printer division. Because Lightning’s POD system plugged into their pre-existing book wholesaling operation, the largest in the country, they offered a compelling value proposition to book publishers for slower-selling titles. Namely, the publisher would provide print files, Lightning would print books in response to orders coming in through the wholesaling business, and Ingram would pay the publishers when the books were sold, after subtracting the printing cost and the normal wholesale discount. No paying for printing books that never sell, no paying for printing months or years before the books sold. Smart. Constructing a printing plant to produce tens of thousands of books a month with an average order quantity of 1.8 copies is a pretty incredible challenge. But because of that connection to distribution in the form of their existing wholesaling business—and plenty of capital—Ingram succeeded where some others failed. In addition, Ingram relentlessly and successfully evangelized POD among publishers, demonstrating to them that titles they formerly would have let go out of print because of the minimum run lengths required for offset printing could be kept in print indefinitely, making authors happier and bringing in more income for all parties.

Our specialty, as previously mentioned, is not POD but SRDP. But as with POD, the economic benefits of SRDP to publishers—minimizing wasted printing and freight—are best realized when combined in some fashion with distribution. So when we had the opportunity to get into the distribution business in 2004, we jumped at it. The opportunity arose when Milt Adams, founder of self-publishing service Beaver’s Pond Press, needed to replace his existing distribution arrangements for some two hundred titles. We hauled his inventory to the Chittenden-Eastman warehouse, stashing it in yet another block of remnant warehouse space. We took over management of Milt’s relationships with book wholesalers and retailers, and began to add other clients in addition to Beaver’s Pond. We named the new operation Itasca Books. Itasca, now managed by former bookseller Mark Jung, is now the second largest part of Bookmobile, with thousands of titles in our warehouse and millions in sales.

Not being satisfied with the number of names we had concocted for the company to date, and in violation of all known branding best-practices, we created a new “umbrella” name, Prism Publishing Center, in 2004. Partly this was to support the promotion of our venture into self-publishing services, spearheaded by former bookseller Maria Manske. Though we published some really good books, this venture ultimately failed to reach breakeven despite Maria’s valiant efforts, and we ceased providing self-publishing services a couple of years later.

We moved from Saint Paul to Saint Louis Park, a suburb of Minneapolis, in January 2005. Incredibly, Dieter, our operations manager, kept the printshop running in two locations during the move. We did not miss a single ship date! 2005 was a year of big growth: we eventually had to move Itasca Books’ warehouse to another location because there was no more space available in our building. Eventually, we were able to bring Itasca’s warehouse back when space opened up, and now the Bookmobile print shop and the Itasca warehouse are adjacent (which was the plan to begin with, in order to realize the benefits of combining SRDP and distribution). While both the print shop and distribution operations continue to provide services independently, we have created a joint Automated Replenishment Program (ARP) service, simplifying the management of just-in-time inventory for scholarly publishers, as well as for independent publishers using direct-to-consumer (D2C) business models. Our D2C services were developed in concert with OR Books, a pioneering publisher founded in New York by two veterans of traditional publishing, John Oakes and Colin Robinson, which has successfully figured out how to make D2C their core business model as a publisher.

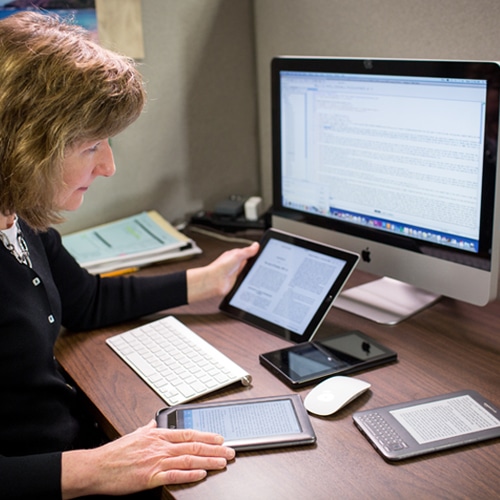

Amy Dvorak tests ebooks on different reading devices, 2014.

eBooks, Round Two

When Jeff Bezos launched the Kindle in November 2007, it became shortly apparent that he had assembled the pieces necessary to make the eBook business work. So as a provider of key services to book publishers, we now were presented with an opportunity to take up where we had left off with Pagewing six years previous. Frankly, I had a bad taste in my mouth after the Pagewing fiasco, but logically, eBook conversion and distribution was a service we were well-placed to offer. My wife Elizabeth encouraged me to move forward. So we did, with the original typesetting and production management department, now run by Rachel Holscher, learning the skills necessary to both make eBooks and distribute them on behalf of publishers. Our eBook service activities grew rapidly over the next five years, and although eBook sales plateaued in 2013-2014, they continue to be a core competency of Rachel’s department and Bookmobile.

Rachel’s department continues to produce print editions for award-winning publishers such as Graywolf Press, Coffee House Press, and Milkweed Editions, as well as provide page composition for clients such as the University of Minnesota Press. The oldest Bookmobile department—which has deep technological roots in the era of phototypesetters, and has grown through the participation of Will Powers with his roots in letterpress printing, also produces interactive content in the newest medium of all: apps for iOS and Android. It turns out that many of the skills that seemed threatened by the rise of digital media—knowledge of typography, an eye for quality, knowing how to produce a project efficiently—matter just as much now as they did in the analog era.

Saint Patrick’s Day 2015

So now, beginning our 34th year, we are much larger than we were when we began, but at 63 employees, still a company small enough to pay attention to quality. The opportunities we see for publishers, and consequently for ourselves, are as big as ever. We see our traditional publisher clients doing very well, and also see new-model publishers like OR Books growing and thriving. We see a rise in really interesting publishing projects in art and photography books, some Kickstarter funded. There is not much loss to the world by the printing of fewer mass-market books, replaced by eBooks. But the flow of beautifully-printed new editions of interesting work by authors, poets, artists and photographers is continuing testimony to the power and importance of the printed book.

Our current staff, and number of years with Bookmobile:

Sarah Purdy, 28

Judy Ogren, 28

Kim Doughty, 20

Mary Oakley, 18

Nicole Baxter, 17

Ann Sudmeier, 16

Rachel Holscher, 16

Kyle Hunter, 16

Tony Houle, 13

Bridgette Buron, 12

Dieter Slezak, 12

Carol Halstead, 11

Paul Trombley, 11

Galen Cruze, 11

Mark Jung, 10

Doug Cox, 10

Eric Holmgren, 10

Tim Navin, 10

Vicki Bonson, 10

Nicole Coggshall, 10

Gretchen Franke, 9

Gary Elwell, 9

Connie Kuhnz, 8

Jennifer Geisinger, 8

Jacalyn Dircks, 8

Nick Vukelich, 8

Chris Franz, 7

Dan Trom, 6

Amy Dvorak, 7

Joni Jensen, 4

Brad Calhoon, 4

Beau Brueggemann, 4

Mischy Ayers, 4

Teng Vang, 4

David Bilotta, 4

Rossanna Castellanos, 4

Blake Filipek, 4

Arna Wilkinson, 4

Heidie Nieling, 4

Gary Kilthau, 4

Chris Shockley, 4

Steve Grobe, 4

Daniel Wigton, 3

Andrea Hamilton, 3

Mark Rask, 2

Patrick Rittmiller, 2

Thomas Waters, 2

Eric Castellanos, 1-1/2

Brenda Khothsombath, 1-1/2

Stephanie Calvit, 1

Devin Koch, 1

Michael Sukowatey, 1

Megan Hurlburt, 1

James Longsdale, 1

Richard Goedeken, 1

Garrett Hansen, 1

Bruce Wilson, 1

Kyle Dahl, 1

Laura Anderson 1,

George Litt, 7 months

James Bengtson-Delaplain, 3 months

Fred Baxter, 1 month