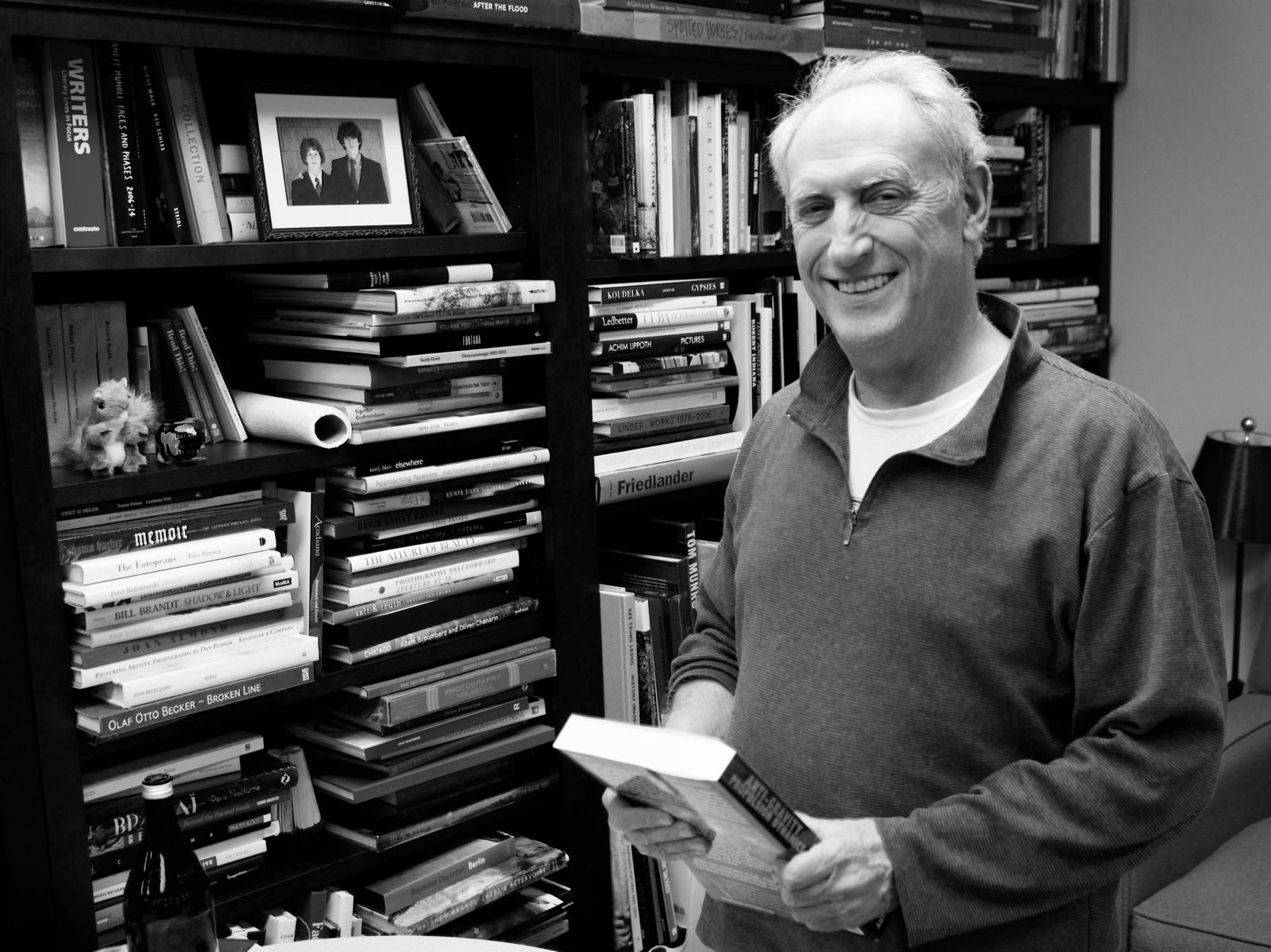

The Bookmobile folks are not the only book people at 5120 Cedar Lake Road. Abraham and Associates, Stu Abraham’s well-known commission sales group, and Nodin Press, a long-time regional and literary publisher run by Norton Stillman, both office here as well. I thought it would be interesting to get their perspectives on the book business. I hope to interview Norton in the next week or so. Here’s the interview I did with Stu last week.

D: What was your first job in the book business?

S: In college, I worked in the University library. Then when I got out of college, I worked at a trade bookstore in Memphis, Tennessee, which is where I’m from. It was an independent bookstore, of the type we used to call “carriage trade”. . . in the sense that it was kind of an upper-crust audience; people would send their drivers over to pick up hardcover mysteries and things like that. And we also had a good literary selection and it was arranged partially by publisher. Like, we had a Grove Press section, and a New Directions section. It was almost all hardcover and some backlist and paperback. [The store] was called the Bookshelf. It was in an area called Poplar Plaza in Memphis.

That was 1975 and 1976. And then, the reason I got interested in sales is, I was basically kind of a screw-up, and never had a job I really liked [laughs], except I enjoyed the bookstore, but I figured out I needed to make more than 90 cents an hour, or whatever it was, a dollar twenty, and I started seeing the sales reps come in and selling books to the owner of the bookshop. I started getting an interest in that, thinking that I could drive from city to city and present books to book buyers, and talk about books, take an inventory, send them into the publisher, go to meetings. I thought maybe this was something I could do.

But then I noticed that there were reps, like the Random House rep and the Simon and Schuster rep, then there were these other reps . . . I found out they were commission reps, and they carried multiple publishers. They were always the more interesting publishers. They would have Farrar Straus, Grove, New Directions. And they didn’t have on a blue blazer and tan pants like the Random House reps, and they drove old Cadillacs and smoked cigars, and they smelled like bourbon when they came in to sell their books in the morning. And then I realized, this is my life goal, is to be a commission rep. And I’ve basically been one ever since [laughs]. I’ve accomplished my goal.

D: So how does it work to be a commission rep?

S: Well, you have contracts with publishers, they’re usually publishers that are not big enough to be able to have a house rep and pay for all of their travel, salary, computer, insurance . . . all the cost of sales. So, as a commission rep we have contracts with multiple publishers and we sell to the bookstores in our territory (ours is 13 states of the Midwest). So we have an exclusive contract with the publisher for all bookstores, book wholesalers, library wholesalers, museum shops, any basically, any kind of retail market for that publisher, and they pay us commission on everything based on what they ship out in that territory of 13 states.

D: So I want to get back to how you made your way up the Mississippi from Memphis to Minneapolis. You identified this job, being a commission rep, but how did you actually get a job as a commission rep?

S: First, nobody would hire me. I was too young, most of the sales reps were older. I had a couple interviews, I never got a job. Then I had an interview as a college book rep, so I was able to land a job with Oxford University Press, as a college book rep, calling on professors, and selling them, like, books on plate tectonics, and things I didn’t know anything about. But, I was hoping to always switch to trade, either with Oxford, or somebody. A friend of mine who was a rep opened up a little distribution company, and they distributed British small presses. It was called Southwest Book Services. And he hired me as a house rep. I was in Chicago then. When I was with Oxford, I was in Detroit. Then I moved to Chicago to work for this company, and that lasted a couple of years, they went out of business. And then, by that time I got to know a bunch of publishers and a bunch of reps, and there was one job opening that I applied for with Grove Press. I flew into to meet with the sales manager, and he and I hit it off instantly, and we’re still friends. We’ve been friends for 35 years. His name is Herman Graf. He managed Grove Press, then he was with Carroll and Graf, with which he was a partner, and now he’s still working. He works for Skyhorse, he’s got an imprint, Herman Graf Books at Skyhorse Books. And so he hired me for Grove Press, and then I used that for my first line, and then I got other lines. But for the first couple of years, the only lines I could get besides Grove were erotica, and left-wing books, and hot remainders that had fallen off the back of some truck [laughter]. Slowly I worked it up to hire people, I brought a partner in, and we hired a couple of people and put a real group together. We started to get more established, important, and prestigious publishers, until we had a real group with really good publishers.

D: Based out of Chicago…

S: Based out of Chicago at the time. My next move was to Minneapolis, which was partly based on personal reasons, but also at that time, B. Dalton was headquartered here and it was owned by the Dayton Hudson Corporation. So that’s why I moved here, partly. And I’ve been here ever since. I got out of the business for a couple years, and then I came back and started all over again in 1992. And since then, for the last almost 25 years I’ve had Abraham Associates.

D: Wow, it’s been that long, mindblowing.

S: Yeah…I started repping in the 70s. I started with Grove Press, I’m thinking ’78 or ’79. So I’ve been doing it [counts off decades] almost 40 years, 37, 38 years. Hard to believe.

D: Okay, so how has being a commission rep changed over that period?

S: Well, in the beginning there were a lot of independent bookstores. Lot of independent bookstores in shopping centers run by people who were like, leaders in their community. Every town had several, and it sort of followed the changes in the book trade. When Barnes & Noble and Borders started expanding, some of those stores closed, and my effort mostly went into calling on Borders. And my group focused on working with all the independents in the territory. And then over that 30 years, there were more closings of independents, more super stores and chains opening. First there was Dalton and Walden, then it was Borders and Barnes & Noble, and then, you know, after 20 more years, those bookstores started scaling back, and now we’re finding the independent bookstores scaling back up. So, as far as how it affected me, I’m back doing what I came up doing, and that’s calling on independent bookstores, and I’m fine with that. I like it.

And, I would like to add, back to the idea of why we’re sitting here talking . . . being in the Bookmobile headquarters, and having an office under the auspices of Bookmobile means a lot to me because it gives me contact with a lot of other elements in the book business. From sitting next to Mark Jung with Itasca, to meeting with you and Nicole and all the people at Bookmobile, sharing information and operational stuff when we can. It’s just a good place for me to be, and it keeps me from being isolated, and I like being here in the middle of Bookmobile which is kind of the capital of the book business in the Twin Cities as I see it. And now Norton Stillman is here too, which makes it even better.

D: Great. I’m going to talk business now. So, how do you actually get paid?

S: Well..basically we get a percentage [from each publisher]. The standard is 10 percent of retail, based on what’s shipped into our states after freight and after returns. And on wholesalers accounts we’re paid five percent commission after returns and freight. So it varies, and if the books don’t sell, we aren’t paid. It’s all based on what customers actually come into the bookstore and buy.

D: And how has that changed over the years? Has it changed? We’re talking about the trade book business here, which, maybe you can talk about what the trade book business is.

S: By trade, I mean retail, college bookstores, independent bookstores, chains, museum shops, and suppliers of libraries.

D: And so over that period of time that you’ve been doing this, has the kind of book that’s being published or the kind of book that sells well changed at all, or is it just random from year to year?

S: I think it’s kind of random from year to year, but the biggest change that I know is that when I first started, independents—and then when they went down, the chains and the ‘superstores’ as we call them—sold a lot of backlist. And we hardly sell any backlist anymore. Everything is computerized. People will order what’s selling, systematically as it sells. But in the beginning I would climb around on the floor looking for my imprints on the books, like a “T” for University of Texas, and a tree for Grove Press, write them up, and then try to write an order for the books that weren’t there. Now we don’t talk about backlists anymore. It’s kind of a shame . . . there’s still a focus on hot recent titles, not deep backlists. You don’t see a lot of deep backlists in bookstores anymore.

D: And you did 30 years ago?

S: Yes. If it was Farrar Straus, or Grove, you would see all their old titles by their classic authors.

D: Does that predate the computerization of bookstores? In other words, now that bookstores can identify what’s turning?

S: I think that’s part of it, because those books didn’t turn probably as well. The superstores carried them because they had 30,000 square feet. The chains with a smaller footprint, Walden and Dalton, didn’t carry much backlist at all. Those were pretty much bestseller and frontlist. Borders & Barnes and Noble did, but then they started scaling back too . . . There are so many editions of backlists, like a lot of editions of Mark Twain, or Shakespeare, you know, the real classics were available so many ways that at one point they had a whole selection of each title. Then they would cut back, cut back. A lot of that was based on sales, and terms, and how well it turned, and they just pared it back.

D: So when I first met you, I didn’t really know any book reps, except David Tripp who had been a college rep. I thought for a while, still do in certain ways, that being a book rep, driving around the countryside, visiting bookstores, having dinner and drinking wine with book people, is, like, the best job in the world.

S: Well that’s why I did it [laughs], and that’s all true—except there’s that romantic side, if you call that romantic, but the flip side of that is you’re alone, you’re often in a small town or a college town, sometimes checking into a cheap motel, and drinking a cheap bottle of wine [laugh], and eating a hamburger, and you have three or four hours of paperwork to do after selling all day. And now it’s all on the computer, but we used to travel around with crates full of paper and order forms and typewriters and stuff.

D: A typewriter, really?

S: I traveled with a typewriter everywhere back then. But that’s what attracted me to it, that you just drive around, you talk about books, you meet people who are interested in books, and I always loved bookstores. I just knew it was an element that I would be comfortable in, and I was a kid, I was 26 years old, but I knew maybe this was my calling. It was either that or psychoanalysis. I thought that this would be more practical and more achievable [laugh].

D: What about now? You mentioned that the indies are coming back. So do you see a revival of that world?

S: I see a revival of that world, it’s not making up in billing, the billing we lost when Borders went out, for example, and some of the bigger chains in the Midwest, like Kroch’s and Brentano’s, and there were more independents, and they were bigger. But there’s a lot of new bookstores; some are niche-y, some are just small, and thankfully some of them are being opened by young people. ‘Cause some of the old bookstores were started in the same period when I started, and those people are now in their sixties and seventies, and there’s a question of what the succession will be with those bookstores. Hopefully they’re turning them over to younger people. But meanwhile, some younger people are opening stores in the Midwest, and in the Twin Cities there’s several good examples of that.

D: What are a couple of examples?

S: Moon Palace is great. That is in the Longfellow neighborhood, I think it is. It’s a great bookstore with wonderful people who really know their books, and spot things ahead and know what to promote and how to sell it. Common Good is a great local store that does a wonderful job, we still have University of Minnesota bookstore, and Magers & Quinn in Minneapolis, I think, is one of the best bookstores in the country, plus, we have what I think are two of the best children’s bookstores in the country, Wild Rumpus, and Red Balloon, one in Minneapolis, one in St. Paul. I don’t see anything that compares to those two stores anywhere.

D: What about elsewhere in your territory, like Chicago or Ann Arbor or Detroit, do you see this revival there as well?

S: Yeah, new stores opening up, really good ones in Chicago, all over town, and some of the older ones are expanding, opening new locations. Detroit has a couple of stores, Ann Arbor has one . . . Ann Arbor, which was dominated by Borders because that’s where their headquarters was. It’s a town that used to have a whole street full of bookstores, State Street, all gone. Now they’re coming back, so Ann Arbor’s reviving too. Other towns, not so much. Like Kansas City doesn’t have a full-service general bookstore. Milwaukee has one great bookstore called Boswell, which is descendent from Harry W. Schwartz booksellers, which was a small chain in Milwaukee that was wonderful. Cincinnati has one, St. Louis has a couple, Wichita . . .

D: So I really only have one more question. I heard about this new chain that’s opening bookstores. I heard there was one in San Diego, one in Seattle, starts with an A, I think…

S: Yeah, I don’t like to say the whole word, that’s enough.

D: What do you think about that?

S: It reminds me of another word that starts with A [laughter]. I don’t think it’s about selling books. I’m not that worried about it as far as the immediate future, but everybody’s speculating, and blogging about it, and everybody has a theory, but the theory that scared me the most, that rings the truest, is—somebody said they’re not going to open bookstores, they’ll probably just buy Macy’s or something, they’ll sell everything. It’s not just about having 200 books faced out. To me these stores are kind of like if you go to the Nike store on Fifth Avenue, it’s not like you’re going to buy your sneakers there. It’s a branding thing, people will go in, and they’re selling the idea of Amazon, and their premium, and their . . .

D: Does Amazon really need branding?

S: Does Nike? I’m speculating too. I think it’s a physical presence. I don’t know if you’d call it branding . . .

D: Yeah it does seem hard to imagine that it’s just about books. It’s never been just about books.

S: No. And a small selection of face-outs that are best sellers is more like a news stand. Why are they doing this? Because I would think they would do something bigger. Meanwhile, he’s shooting spaceships up into the outer atmosphere. I don’t think he cares about a small bookshop.

D: I just had one thought, no idea whether it means anything or not, but one gripe about self-publishing for Amazon is the difficulty of getting your books into physical bookstores. [True.] Whereas if Amazon has its own physical bookstores, it reduces that count against self-publishing through Amazon.

S: But could that pay off for Amazon? I don’t know . . . Yeah, that would be an advantage, they have so many self-published books, maybe they could have the local authors featured there . . . It would be interesting to see the inventory but I think it’s the top sellers from the publishers that they would call the best partners, that would be a nice way to put it. The best publishers with the best terms, best marketing fees, and all that stuff.

D: The most kickbacks.

S: Most kickbacks, yes . . . Maybe it will be like a store of the future, like they’ve done a couple of test designs in England where they have covers, and you push a button to order the eBook.

D: Or a book printed on the spot, something we talked about 20 years ago.

S: Right, exactly . . . Why carry books at all? They can print them, or you can push a button and get it downloaded. They can print it—in fact that’s not a new idea. We had it a long time ago. But they have the money to do it. But books, what’s the big deal about books? How come everybody wants to mess with books? It’s not like we’re making a fortune [laughs]. The idea of them buying Federated or Macy’s . . . to sell everything. They have websites and you can buy something, return it to the store, change the size . . .

D: They could have their pick of retailing chains, I would think. Any one of those department stores.

S: Anyway, I’m glad I’m here at Bookmobile, and I’m glad I’m in business, and I hope to be here for a lot longer, and I’m glad to be here with you, and the whole Bookmobile gang, and Mark, and I’m looking forward to the future.

Need a printing quote, eBook conversion quote, or more information?

You can request a printing quote here, or request an eBook conversion quote here.

I’d be happy to answer questions—you can contact me via email. I welcome any feedback, including that pointing out my errors!

Don Leeper is founder and CEO of Bookmobile, which has provided design, printing, eBook, and distribution services for book publishers since 1982.