Film lamination is important for paperback covers and dust jackets. Books get banged around a lot en route from printer to reader (see my post on cartons). Without cover lamination, corners get bent, the printed image scuffs and cracks, and other mayhem ensues. Nothing else really does the job like film lamination. UV coating is not nearly as protective. In my early days as a print buyer, I inherited an account where the publisher had frequently used UV coating instead of lamination to save money. After multiple acrimonious go-arounds with the printer about cover damage, doing Taber tests*, etc., the publisher and I mutually agreed it would be better to spend the money on lamination than get all those banged up books. That said, we have publisher clients who still choose UV over lamination to achieve a certain “uncoated” look in the printed cover. In making this aesthetic decision, they are fully aware of the trade-offs in durability.

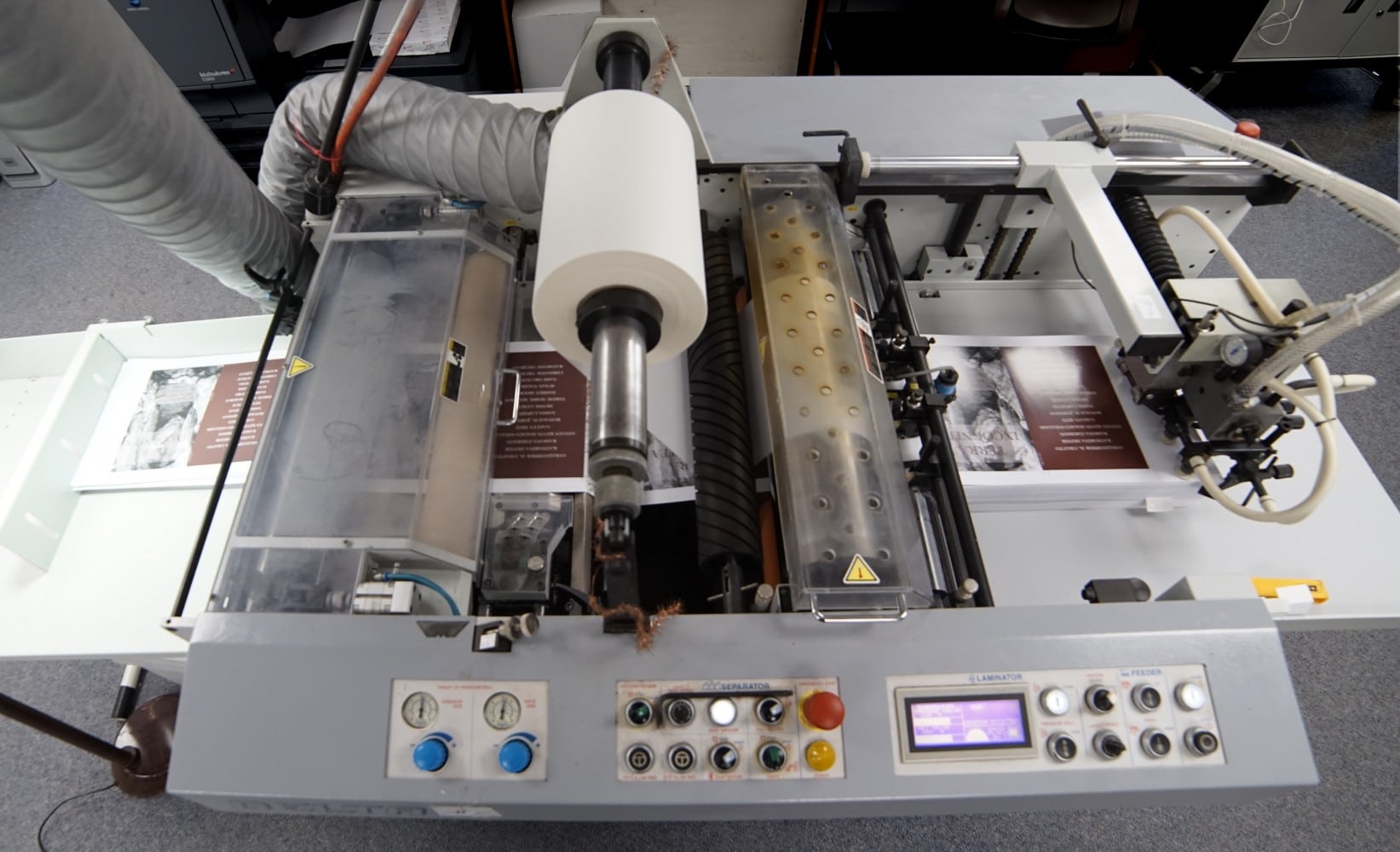

What is film lamination? Film lamination is a thin film of polypropylene, polyester or nylon which comes off a roll and is pressed evenly onto the printed cover by a heated roller on a laminating machine. By thin I mean 1-2 mils. A mil is a thousandth of an inch. We’re not talking about a lot of plastic here. The heat and pressure of the roller, along with adhesives, make the laminate film stick to the cover—or it is supposed to. The double-sided laminating machines you see in copy shops use laminate film on both sides of the sheet being laminated: the overlapping edges of the two sheets of laminate film stick to each other. The single-sided laminate on a book cover has to stick to the cover itself, not to another sheet of lamination film.

Besides durability, lamination can also improve the aesthetic quality of a cover. Printed covers fresh off the offset press or digital printer may have different reflectivity in different areas of the image depending on ink or toner coverage: lamination provides a single reflective surface. Gloss lamination tends to brighten—or at least not tone down—an image, while matte lamination provides an attractive non-reflective surface. And this brings us to the first issues that can arise with lamination: its affect on the printed image.

If your cover design has heavy coverage of dark colors, gloss lamination helps keep the colors dark and rich. However, gloss lamination shows fingerprints, especially over continuous areas of dark colors or black. Matte lamination, on the other hand, is less likely to show fingerprints and helps reduce reflections, but it also subdues the richness of a dark black or other dark color under most lighting conditions: a rich black can turn into a boring gray. Pick your poison: either option can protect and enhance a book cover.

For digital printing, heavy coverage affects the lamination in another way: it rebels against sticking to the cover. This is really bad, and there is really nothing more disheartening to see than a brand new book with the lamination peeling up at the edges: so damned cheesy.

The reason the lamination doesn’t want to stick lies in the nature of the digital printing process. Historically, digital printing machines use small amounts of silicone oil (fuser oil) in the process of laying down the image on paper. The fuser oil provides a glossy surface to the image, reduces static build up in the printer (which helps reduce jams) and lubricates parts as the paper moves through the hot components of the machine. Unfortunately, binder glue hates fuser oil, and the adhesive on lamination film hates fuser oil. Early color printers—the kind that could print a high quality cover image—used a lot of fuser oil. We started printing books on digital printing equipment in 1996, well before most outfits, and one of the biggest challenges in the early years was getting lamination film to stick the covers. It just hates that fuser oil! The solution turned out to be a judicious mix of adjusting the speed and temperature of the lamination machine, and, very importantly, picking the right brand and type of lamination film. The film manufacturers started making superstick types of film, which was helpful.

While the trend has been for newer color printers to use less fuser oil, the issue remains, and some of the big names in color digital printers still use a lot of fuser oil. This affects what lamination films a digital book printer can use. Some films with attractive properties may not be usable because they won’t stick to the digitally printed covers.

One such attractive property is scuff resistance in matte lamination film. The scuffing of matte laminated covers is an ongoing issue. With most matte films, a fingernail or other hard object brushed across the cover can produce a visible scuff. Even some packing materials, such as styrofoam, are abrasive enough to damage the cover as the book is jostled cross country in the back of a semi. Again, the visibility of scuffing partly depends on the cover design: with heavy ink/toner coverage, scuffing is more visible. This scuffing is why we recommend that books with matte-laminated covers be shrink-wrapped.

We test new materials all the time, and one of them is so-called scuff-resistant matte lamination film. Notice it is called scuff-resistant: there is no such thing as scuff-proof lamination. Also, scuff-resistant films are not “lay flat,” a term that means the film helps resist cover curl. So far, we have not found a scuff-resistant matte lamination that will stick to our digitally printed covers. However, we have a new color printer that uses much less fuser oil than our previous printer, and we are currently testing scuff-resistant films. The scuff-resistant film is more expensive than the normal matte film. Between the additional expense and the risk of curl–which is usually much more of an issue than scuffing–scuff-resistant film may wind up being something you choose not to use.

As with everything in our manufacturing process, it becomes a trade-off: are our customers willing to pay a few cents more per book to solve an issue? Well, honestly, it depends on the publisher and their philosophy of print buying. Such philosophies can vary, justifiably. (May be another blog post there.) Speaking of dollars and cents, the cost of a roll of lay-flat matte lamination film for digital printing is about twice as that of a roll of gloss film.

Another important property of a lamination film is the ability to minimize cover curl. I remember walking into the late, great indy bookstore in Saint Paul, the Hungry Mind, on a humid August afternoon: every cover on the face-out new releases shelf was standing at attention. The books might have been printed in Michigan or Pennsylvania or Minnesota in February, when the air is dry as a bone. Lamination was applied to the dry cover, the books were bound, trimmed and packed, only to be opened in a Midwestern summer environment of super-high humidity. The paper stock of the cover absorbed moisture from the air and expanded across the grain. Lamination film does not absorb moisture to the same degree, and therefore does not expand. The width of the inside cover increases while the outside width stays the same. The result is a cover curling up off the first page of the book.

As with many aspects of making a physical object like a book, it is all a matter of degree. A print shop with a humidity-regulated print room and bindery will reduce curl, but not eliminate it. Inducing some inward curl by tensioning the lamination film during the lamination process can help: but too much inward curl is not a good thing either. Finally, so-called lay-flat lamination helps. Lay-flat lamination is made of nylon, which is more permeable to water molecules in the air than the alternative polypropylene or polyester films.

As always, our goal is to achieve high-quality printed books. Often quality costs more, and we are either willing to absorb the cost (as with our doublewall cartons), or we feel we can charge the customer a little bit more. Sometimes quality does not actually cost more: it just means paying attention. Quality lamination is a mix of both: good materials plus paying attention. Also we must factor in risk: if using a material that seems to solve one problem (matte film scuffing), merely results in a more drastic problem (the film peeling off, or cover curling), we’re going to go the route that is the best bet, while continuing to explore the issue by testing new materials.

Production Tips: Film Lamination

- Choose lay-flat lamination film–gloss or matte–for the best combination of curl-resistance, protection, and attractiveness for paperback covers. Be aware that humidity extremes can still cause cover curl.

- Don’t be surprised to see fingerprints on gloss lamination or scuffing on matte lamination over rich blacks and dark colors. Ideally, the book designer should take this into account.

*A Taber test refers to testing a material for resistance to abrasion on a special machine made by Taber Industries.