But how was it made? Inside the world’s oldest multicolor printed book

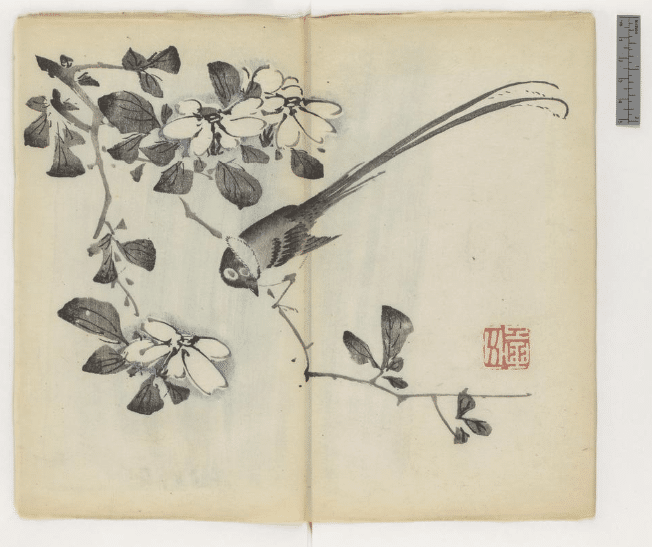

Seeing this headline on CNN, I had to read the article! Titled Shi zhu zhai shu hua pu, the book was printed in China in the early 17th century, and it gives instruction in the arts of calligraphy and brush painting,

CNN relates that curators at the Cambridge University Press painstakingly opened the book page by page over fourteen days and made digital images, which you can view online. There are 138 illustrated pages and 250 pages of text. The illustrated pages are exquisite: each spread is a unique, flowing composition, not forced into a rigid grid. The edges of the pages themselves are the only rectilinear elements. The images have the subtlety of watercolors. Having to guess and not knowing the age of the book*, I would have thought the printing technique was stone lithography, which can produce very fine gradations and tones. In fact, though, the book was printed from engraved wood blocks. While CNN claims it’s the world’s oldest multicolor printed book, the curators claim only that it is the “earliest Chinese book printed by the technique of polychrome xylography.”

CNN quotes the head of the Chinese Department at the library as saying that the technique was “so refined and so complex that it was never subsequently equaled.” Pretty amazing piece of work, indeed. Actually, though, fine multicolor wood engraving is alive and well in 2015 and living in Wisconsin in the person of Gaylord Schanilec. (See this NY Times article, and Schanilec’s website.) Whether or not Schanilec’s work “equals” the Chinese book I would not even presume to consider without having both works right in front of me in good light. Web images do not do fine printing justice. I have a copy of one of Schanilec’s earlier works, High Bridge (1987), and digital images of its pages just don’t convey the delicacy of the engraving, the subtlety of the colors and the impress of the wooden plates.

Schanilec—who once did freelance work for Bookmobile—lives in Stockholm, Wisconsin, a tiny town nestled under the bluffs on the eastern shore of Lake Pepin, a 22-mile-long widening of the Mississippi River. His latest book is what the New York Times called an “ode” to the lake, titled Lac Des Pleurs.

Lake Pepin was formed by sediment from the tributary Chippewa River that blocked the main channel of the Mississippi. On the Minnesota side runs Highway 61—yes, that Highway 61—and on the Wisconsin side runs WIS 35 through the little towns of Bay City, Maiden Rock, Stockholm and Pepin. The highway swoops high above the lake under limestone cliffs where bald eagles and turkey vultures soar on the thermals of sunny days. Innumerable ravines and valleys cut by springfed streams—brook trout live here—are densely wooded with sugar maple and basswood. In the depths of the big river, fish more mysterious than trout abound: paddlefish, big mouth buffalo, giant catfish. In the summer the lake glitters in the afternoon sun, and in the wintertime it forms a miles-long ribbon of snow-covered ice. The names of the towns echo the spangled human history of the valley: Wabash and Red Wing were Dakota leaders, Stockholm was founded by Swedish immigrants in 1854, Frontenac was named for a French colonial governor of Canada from the 1600s.

The title of Schanilec’s book, Lac Des Pleurs, lake of tears, is the name that the early French explorer Father Louis Hennepin gave to Pepin because of the tears shed by Dakota warriors when they were prevented from murdering him and his companions. Whatever the truth of the warriors’ tears—Hennepin was prone to what might charitably be called invention, for instance claiming that he descended the entire Mississippi in 30 days—it is a beautiful name. But the name that stuck was Pepin, after the early French settler Jean Pepin.

Schanilec printed Lac Des Pleurs in an edition of 100. It took him seven years. He used a boat fitted with an easel, as well as a digital camera, to acquire source imagery. He did extensive library and archival research, as well as consulting with biologists and historians. The wood he used for plates was maple he harvested himself.

Detail from map accompanying Lac Des Pleurs. Map is printed from wood engravings, labels are letterpress.

While the book itself is a tour de force, the accompanying map, printed in two parts utilizing both wood engraving and letterpress type, is mind boggling to anybody who’s ever done any hand printing. Not only are the map features meticulously engraved on giant (giant for wood engraving) maple endgrain plates, the labels and legend are hand set in metal type. If you’ve ever set metal type on a composing stick, imagine the challenges of setting the label for the Zumbro River following the sinuous course of the river itself on a map.

You can see more about Lac Des Pleurs at Schanilec’s website, as well as follow much of the story of the making of the book on his blog.

Most of the run of 100 are sold, but there are still copies available at $7,800 each. Expensive, but in this case the eBook will not suffice.

Kidding—there is no eBook.

Ars longa, vita brevis

There are two interpretations of this aphorism, which is a Latin translation of a Greek original by Hippocrates. A common interpretation is that art lasts forever, while the life of the artist is short. Some argue that a more accurate translation, based on Hippocrates Greek original, is that life is short, and it takes a long time to acquire art, in the sense of expertise or skill.

It seems to me that both interpretations resonate in the context of these two great books, whether works of art or works of artisanry. First, we have the good fortune to appreciate works of art hundreds, even thousands, of years after they were created and their creators long gone—as our descendants hopefully will Lac Des Pleurs. Second, the commitment of time to acquire the skill to create either book is in fact a sizable proportion of an artist’s lifetime.

Need a printing quote, eBook conversion quote, or more information?

You can request a printing quote here, or request an eBook conversion quote here.

I’d be happy to answer questions—you can contact me via email. I welcome any feedback, including that pointing out my errors!

Don Leeper is founder and CEO of Bookmobile, which has provided design, printing, eBook and distribution services for book publishers since 1982.

*Stone lithography was invented in 1796 in Germany by Alois Senefelder, long after the Chinese book was printed.